33 More Amazing And Disturbing Photos From History's Vaults

Some more of the most Influential photographs ever taken, with a little bit of backstory included.

- List View

- Player View

- Grid View

Advertisement

-

1.

The Valley Of The Shadow Of Death, Roger Fenton, 1855. While little is remembered of the Crimean War—that nearly three-year conflict that pitted England, France, Turkey and Sardinia-Piedmont against Russia—coverage of it radically changed the way we view war. Until then, the general public learned of battles through heroic paintings and illustrations. But after the British photographer Roger Fenton landed in 1855 on that far-off peninsula on the Black Sea, he sent back revelatory views of the conflict that firmly established the tradition of war photography. Those 360 photos of camp life and men manning mortar batteries may lack the visceral brutality we have since become accustomed to, yet Fenton’s work showed that this new artistic medium could rival the fine arts. This is especially clear in The Valley of the Shadow of Death, which shows a cannonball-strewn gully not far from the spot immortalized in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” That haunting image, which for many evokes the poem’s “Cannon to right of them,/ Cannon to left of them,/ Cannon in front of them” as the troops race “into the valley of Death,” also revealed to the general public the reality of the lifeless desolation left in the wake of senseless slaughter. Scholars long believed that this was Fenton’s only image of the valley. But a second version with fewer of the scattered projectiles turned up in 1981, fueling a fierce debate over which came first. That the more recently discovered picture is thought to be the first indicates that Fenton may have been one of the earliest to stage a news photograph.

The Valley Of The Shadow Of Death, Roger Fenton, 1855. While little is remembered of the Crimean War—that nearly three-year conflict that pitted England, France, Turkey and Sardinia-Piedmont against Russia—coverage of it radically changed the way we view war. Until then, the general public learned of battles through heroic paintings and illustrations. But after the British photographer Roger Fenton landed in 1855 on that far-off peninsula on the Black Sea, he sent back revelatory views of the conflict that firmly established the tradition of war photography. Those 360 photos of camp life and men manning mortar batteries may lack the visceral brutality we have since become accustomed to, yet Fenton’s work showed that this new artistic medium could rival the fine arts. This is especially clear in The Valley of the Shadow of Death, which shows a cannonball-strewn gully not far from the spot immortalized in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” That haunting image, which for many evokes the poem’s “Cannon to right of them,/ Cannon to left of them,/ Cannon in front of them” as the troops race “into the valley of Death,” also revealed to the general public the reality of the lifeless desolation left in the wake of senseless slaughter. Scholars long believed that this was Fenton’s only image of the valley. But a second version with fewer of the scattered projectiles turned up in 1981, fueling a fierce debate over which came first. That the more recently discovered picture is thought to be the first indicates that Fenton may have been one of the earliest to stage a news photograph. -

2.

Michael Jordan, Co Rentmeester, 1984. It may be the most famous silhouette ever photographed. Shooting Michael Jordan for LIFE in 1984, Jacobus “Co” Rentmeester captured the basketball star soaring through the air for a dunk, legs split like a ballet dancer’s and left arm stretched to the stars. A beautiful image, but one unlikely to have endured had Nike not devised a logo for its young star that bore a striking resemblance to the photo. Seeking design inspiration for its first Air Jordan sneakers, Nike paid Rentmeester $150 for temporary use of his slides from the life shoot. Soon, “Jumpman” was etched onto shoes, clothing and bedroom walls around the world, eventually becoming one of the most popular commercial icons of all time. With Jumpman, Nike created the concept of athletes as valuable commercial properties unto themselves. The Air Jordan brand, which today features other superstar pitchmen, earned $3.2 billion in 2014. Rentmeester, meanwhile, has sued Nike for copyright infringement. No matter the outcome, it’s clear his image captures the ascendance of sports celebrity into a multibillion-dollar business, and it’s still taking off.

Michael Jordan, Co Rentmeester, 1984. It may be the most famous silhouette ever photographed. Shooting Michael Jordan for LIFE in 1984, Jacobus “Co” Rentmeester captured the basketball star soaring through the air for a dunk, legs split like a ballet dancer’s and left arm stretched to the stars. A beautiful image, but one unlikely to have endured had Nike not devised a logo for its young star that bore a striking resemblance to the photo. Seeking design inspiration for its first Air Jordan sneakers, Nike paid Rentmeester $150 for temporary use of his slides from the life shoot. Soon, “Jumpman” was etched onto shoes, clothing and bedroom walls around the world, eventually becoming one of the most popular commercial icons of all time. With Jumpman, Nike created the concept of athletes as valuable commercial properties unto themselves. The Air Jordan brand, which today features other superstar pitchmen, earned $3.2 billion in 2014. Rentmeester, meanwhile, has sued Nike for copyright infringement. No matter the outcome, it’s clear his image captures the ascendance of sports celebrity into a multibillion-dollar business, and it’s still taking off. -

3.

Dovima With Elephants, Paris, August, Richard Avedon, 1955. When Richard Avedon photographed Dovima at a Paris circus in 1955 for Harper’s Bazaar, both were already prominent in their fields. She was one of the world’s most famous models, and he was one of the most famous fashion photographers. It makes sense, then, that Dovima With Elephants is one of the most famous fashion photographs of all time. But its enduring influence lies as much in what it captures as in the two people who made it. Dovima was one of the last great models of the sophisticated mold, when haute couture was a relatively cloistered and elite world. After the 1950s, models began to gravitate toward girl-next-door looks instead of the old generation’s unattainable beauty, helping turn high fashion into entertainment. Dovima With Elephants distills that shift by juxtaposing the spectacle and strength of the elephants with Dovima’s beauty—and the delicacy of her gown, which was the first Dior dress designed by Yves Saint Laurent. The picture also brings movement to a medium that was previously typified by stillness. Models had long been mannequins, meant to stand still while the clothes got all the attention. Avedon saw what was wrong with that equation: clothes didn’t just make the man; the man also made the clothes. And by moving models out of the studio and placing them against exciting backdrops, he helped blur the line between commercial fashion photography and art. In that way, Dovima With Elephants captures a turning point in our broader culture: the last old-style model, setting fashion off on its new path.

Dovima With Elephants, Paris, August, Richard Avedon, 1955. When Richard Avedon photographed Dovima at a Paris circus in 1955 for Harper’s Bazaar, both were already prominent in their fields. She was one of the world’s most famous models, and he was one of the most famous fashion photographers. It makes sense, then, that Dovima With Elephants is one of the most famous fashion photographs of all time. But its enduring influence lies as much in what it captures as in the two people who made it. Dovima was one of the last great models of the sophisticated mold, when haute couture was a relatively cloistered and elite world. After the 1950s, models began to gravitate toward girl-next-door looks instead of the old generation’s unattainable beauty, helping turn high fashion into entertainment. Dovima With Elephants distills that shift by juxtaposing the spectacle and strength of the elephants with Dovima’s beauty—and the delicacy of her gown, which was the first Dior dress designed by Yves Saint Laurent. The picture also brings movement to a medium that was previously typified by stillness. Models had long been mannequins, meant to stand still while the clothes got all the attention. Avedon saw what was wrong with that equation: clothes didn’t just make the man; the man also made the clothes. And by moving models out of the studio and placing them against exciting backdrops, he helped blur the line between commercial fashion photography and art. In that way, Dovima With Elephants captures a turning point in our broader culture: the last old-style model, setting fashion off on its new path. -

4.

Coffin Ban, Tami Silicio, 2004. By April 2004, some 700 U.S. troops had been killed on the battlefield in Iraq, but images of the dead returning home in coffins were never seen. The U.S. government had banned news organizations from photographing such scenes in 1991, arguing that they violated families’ privacy and the dignity of the dead. To critics, the policy was simply a way of sanitizing an increasingly bloody conflict. As a government contractor working for a cargo company in Kuwait, Tami Silicio was moved by the increasingly human freight she was loading and felt compelled to share what she was seeing. On April 7, Silicio used her Nikon Coolpix to photograph more than 20 flag-draped coffins as they passed through Kuwait on their way to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. She emailed the picture to a friend in the U.S., who forwarded it to a photo editor at the Seattle Times. With Silicio’s permission, the Times put the photo on its front page on April 18—and immediately set off a firestorm. Within days, Silicio was fired from her job and a debate raged over the ethics of publishing the images. While the government claimed that families of troops killed in action agreed with its policy, many felt that the pictures should not be censored. In late 2009, during President Barack Obama’s first year in office, the Pentagon lifted the ban.

Coffin Ban, Tami Silicio, 2004. By April 2004, some 700 U.S. troops had been killed on the battlefield in Iraq, but images of the dead returning home in coffins were never seen. The U.S. government had banned news organizations from photographing such scenes in 1991, arguing that they violated families’ privacy and the dignity of the dead. To critics, the policy was simply a way of sanitizing an increasingly bloody conflict. As a government contractor working for a cargo company in Kuwait, Tami Silicio was moved by the increasingly human freight she was loading and felt compelled to share what she was seeing. On April 7, Silicio used her Nikon Coolpix to photograph more than 20 flag-draped coffins as they passed through Kuwait on their way to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. She emailed the picture to a friend in the U.S., who forwarded it to a photo editor at the Seattle Times. With Silicio’s permission, the Times put the photo on its front page on April 18—and immediately set off a firestorm. Within days, Silicio was fired from her job and a debate raged over the ethics of publishing the images. While the government claimed that families of troops killed in action agreed with its policy, many felt that the pictures should not be censored. In late 2009, during President Barack Obama’s first year in office, the Pentagon lifted the ban. -

5.

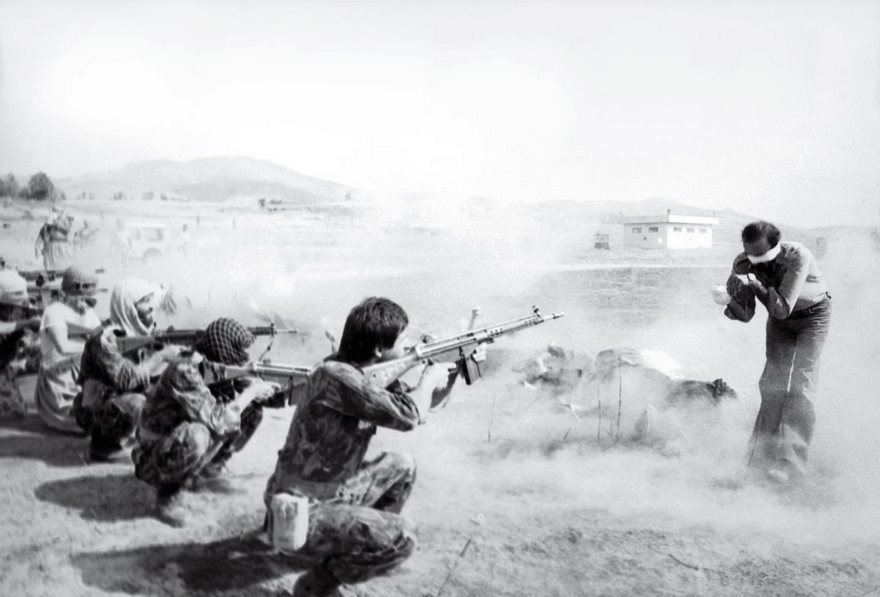

Firing Squad In Iran, Jahangir Razmi, 1979. Few images are as stark as one of an execution. On August 27, 1979, 11 men who had been convicted of being “counterrevolutionary” by the regime of Iranian ruler Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini were lined up on a dirt field at Sanandaj Airport and gunned down side by side. No international journalists witnessed the killings. They had been banned from Iran by Khomeini, which meant it was up to the domestic press to chronicle the bloody conflict between the theocracy and the local Kurds, who had been denied representation in Khomeini’s government. The Iranian photographer Jahangir Razmi had been tipped off to the trial, and he shot two rolls of film at the executions. One image, with bodies crumpled on the ground and another man moments from joining them, was published anonymously on the front page of the Iranian daily Ettela’at. Within hours, members of the Islamic Revolutionary Council appeared at the paper’s office and demanded the photographer’s name. The editor refused. Days later, the picture was picked up by the news service UPI and trumpeted in papers around the world as evidence of the murderous nature of Khomeini’s brand of religious government. The following year, Firing Squad in Iran was awarded the Pulitzer Prize—the only anonymous winner in history. It was not until 2006 that Razmi was revealed as the photographer.

Firing Squad In Iran, Jahangir Razmi, 1979. Few images are as stark as one of an execution. On August 27, 1979, 11 men who had been convicted of being “counterrevolutionary” by the regime of Iranian ruler Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini were lined up on a dirt field at Sanandaj Airport and gunned down side by side. No international journalists witnessed the killings. They had been banned from Iran by Khomeini, which meant it was up to the domestic press to chronicle the bloody conflict between the theocracy and the local Kurds, who had been denied representation in Khomeini’s government. The Iranian photographer Jahangir Razmi had been tipped off to the trial, and he shot two rolls of film at the executions. One image, with bodies crumpled on the ground and another man moments from joining them, was published anonymously on the front page of the Iranian daily Ettela’at. Within hours, members of the Islamic Revolutionary Council appeared at the paper’s office and demanded the photographer’s name. The editor refused. Days later, the picture was picked up by the news service UPI and trumpeted in papers around the world as evidence of the murderous nature of Khomeini’s brand of religious government. The following year, Firing Squad in Iran was awarded the Pulitzer Prize—the only anonymous winner in history. It was not until 2006 that Razmi was revealed as the photographer. -

6.

Boat Of No Smiles, Eddie Adams, 1977. It’s easy to ignore the plight of refugees. They are seen as numbers more than people, moving from one distant land to the next. But a picture can puncture that illusion. The sun hadn’t yet risen on Thanksgiving Day in 1977 when Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams watched a fishing boat packed with South Vietnamese refugees drift toward Thailand. He was on patrol with Thai maritime authorities as the unstable vessel carrying about 50 people came to shore after days at sea. Thousands of refugees had streamed from postwar Vietnam since the American withdrawal more than two years earlier, fleeing communism by fanning out across Southeast Asia in search of safe harbor. Often they were pushed back into the abyss and told to go somewhere else. Adams boarded the packed fishing boat and began shooting. He didn’t have long. Eventually Thai authorities demanded that he disembark—wary, Adams believed, that his presence would create sympathy for the refugees that might compel Thailand to open its doors. On that score, they were right. Adams transmitted his pictures and wrote a short report, and within days they were published widely. The images were presented to Congress, helping to open the doors for more than 200,000 refugees from Vietnam to enter the U.S. from 1978 to 1981. “The pictures did it,” Adams said, “pushed it over.”

Boat Of No Smiles, Eddie Adams, 1977. It’s easy to ignore the plight of refugees. They are seen as numbers more than people, moving from one distant land to the next. But a picture can puncture that illusion. The sun hadn’t yet risen on Thanksgiving Day in 1977 when Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams watched a fishing boat packed with South Vietnamese refugees drift toward Thailand. He was on patrol with Thai maritime authorities as the unstable vessel carrying about 50 people came to shore after days at sea. Thousands of refugees had streamed from postwar Vietnam since the American withdrawal more than two years earlier, fleeing communism by fanning out across Southeast Asia in search of safe harbor. Often they were pushed back into the abyss and told to go somewhere else. Adams boarded the packed fishing boat and began shooting. He didn’t have long. Eventually Thai authorities demanded that he disembark—wary, Adams believed, that his presence would create sympathy for the refugees that might compel Thailand to open its doors. On that score, they were right. Adams transmitted his pictures and wrote a short report, and within days they were published widely. The images were presented to Congress, helping to open the doors for more than 200,000 refugees from Vietnam to enter the U.S. from 1978 to 1981. “The pictures did it,” Adams said, “pushed it over.” -

7.

Country Doctor, W. Eugene Smith, 1948. Although lauded for his war photography, W. Eugene Smith left his most enduring mark with a series of midcentury photo essays for LIFE magazine. The Wichita, Kans.–born photographer spent weeks immersing himself in his subjects’ lives, from a South Carolina nurse-midwife to the residents of a Spanish village. His aim was to see the world from the perspective of his subjects—and to compel viewers to do the same. “I do not seek to possess my subject but rather to give myself to it,” he said of his approach. Nowhere was this clearer than in his landmark photo essay “Country Doctor.” Smith spent 23 days with Dr. Ernest Ceriani in and around Kremmling, Colo., trailing the hardy physician through the ranching community of 2,000 souls beneath the Rocky Mountains. He watched him tend to infants, deliver injections in the backseats of cars, develop his own x-rays, treat a man with a heart attack and then phone a priest to give last rites. By digging so deeply into his assignment, Smith created a singular, starkly intimate glimpse into the life of a remarkable man. It became not only the most influential photo essay in history but the aspirational template for the form.

Country Doctor, W. Eugene Smith, 1948. Although lauded for his war photography, W. Eugene Smith left his most enduring mark with a series of midcentury photo essays for LIFE magazine. The Wichita, Kans.–born photographer spent weeks immersing himself in his subjects’ lives, from a South Carolina nurse-midwife to the residents of a Spanish village. His aim was to see the world from the perspective of his subjects—and to compel viewers to do the same. “I do not seek to possess my subject but rather to give myself to it,” he said of his approach. Nowhere was this clearer than in his landmark photo essay “Country Doctor.” Smith spent 23 days with Dr. Ernest Ceriani in and around Kremmling, Colo., trailing the hardy physician through the ranching community of 2,000 souls beneath the Rocky Mountains. He watched him tend to infants, deliver injections in the backseats of cars, develop his own x-rays, treat a man with a heart attack and then phone a priest to give last rites. By digging so deeply into his assignment, Smith created a singular, starkly intimate glimpse into the life of a remarkable man. It became not only the most influential photo essay in history but the aspirational template for the form. -

8.

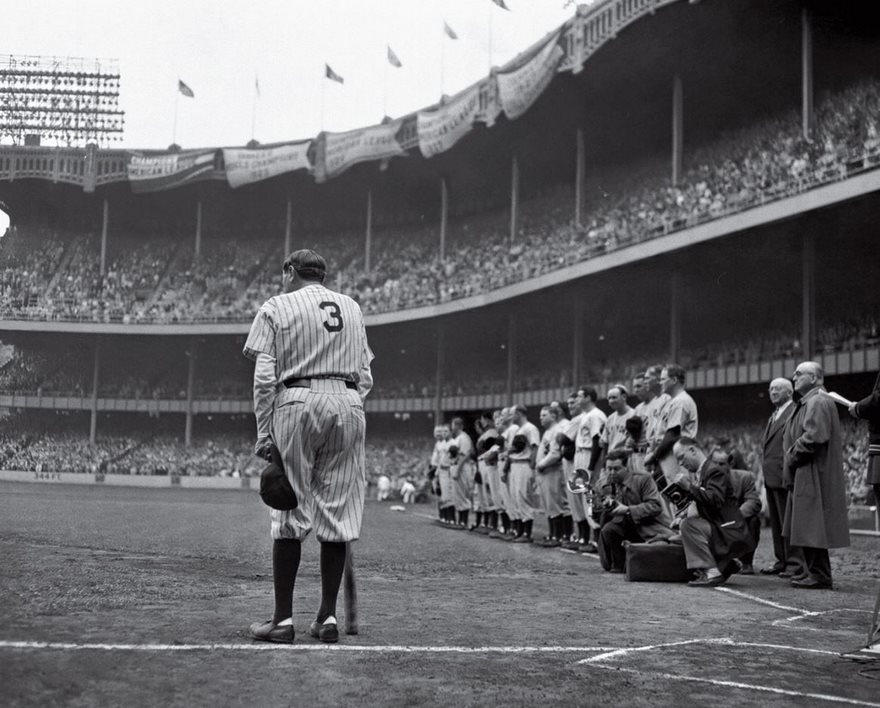

The Babe Bows Out, Nat Fein, 1948. He was the greatest ballplayer of them all, the towering Sultan of Swat. But by 1948, Babe Ruth had been out of the game for more than a decade and was struggling with terminal cancer. So when the beloved Bambino stood before a massive crowd on June 13 to help celebrate the silver anniversary of Yankee Stadium—known to all in attendance as the House That Ruth Built—and to retire his No. 3, it was clear this was a final public goodbye. Nat Fein of the New York Herald Tribune was one of dozens of photographers staked out along the first-base line. But as the sound of “Auld Lang Syne” filled the stadium, Fein “got a feeling” and walked behind Ruth, where he saw the proud ballplayer leaning on a bat, his thin legs hinting at the toll the disease had wreaked on his body. From that spot, Fein captured the almost mythic role that athletes play in our lives—even at their weakest, they loom large. Two months later Ruth was dead, and Fein went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for his picture. It was the first one awarded to a sports photographer, giving critical legitimacy to a form other than hard-news reportage.

The Babe Bows Out, Nat Fein, 1948. He was the greatest ballplayer of them all, the towering Sultan of Swat. But by 1948, Babe Ruth had been out of the game for more than a decade and was struggling with terminal cancer. So when the beloved Bambino stood before a massive crowd on June 13 to help celebrate the silver anniversary of Yankee Stadium—known to all in attendance as the House That Ruth Built—and to retire his No. 3, it was clear this was a final public goodbye. Nat Fein of the New York Herald Tribune was one of dozens of photographers staked out along the first-base line. But as the sound of “Auld Lang Syne” filled the stadium, Fein “got a feeling” and walked behind Ruth, where he saw the proud ballplayer leaning on a bat, his thin legs hinting at the toll the disease had wreaked on his body. From that spot, Fein captured the almost mythic role that athletes play in our lives—even at their weakest, they loom large. Two months later Ruth was dead, and Fein went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for his picture. It was the first one awarded to a sports photographer, giving critical legitimacy to a form other than hard-news reportage. -

9.

Camelot, Hy Peskin, 1953. Before they could become American royalty, America needed to meet John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Jacqueline Lee Bouvier. That introduction came when Hy Peskin photographed the handsome politician on the make and his radiant fiancée over a summer weekend in 1953. Peskin, a renowned sports photographer, headed to Hyannis Port, Mass., at the invitation of family patriarch Joseph Kennedy. The ambassador, eager for his son to take the stage as a national figure, thought a feature in the pages of LIFE would foster a fascination with John, his pretty girlfriend and one of America’s wealthiest families. That it did. Peskin put together a somewhat contrived “behind the scenes” series titled “Senator Kennedy Goes A-Courting.” While Jackie bristled at the intrusion—John’s mother Rose even told her how to pose—she went along with the staging, and readers got to observe Jackie mussing the hair of “the handsomest young member of the U.S. Senate,” playing football and softball with her future in-laws, and sailing aboard John’s boat, Victura. “They just shoved me into that boat long enough to take the picture,” she later confided to a friend. It was pitch-perfect brand making, with Kennedy on the cover of the world’s most widely read photo magazine, cast as a self-assured playboy prepared to say goodbye to bachelorhood. A few months later LIFE would cover the couple’s wedding, and by then America was captivated. In the staid age of Dwight David Eisenhower and Richard Milhous Nixon, Peskin unveiled the face of Camelot, one that changed America’s perception of politics and politicians, and set John and Jackie off on becoming the most recognizable couple on the planet.

Camelot, Hy Peskin, 1953. Before they could become American royalty, America needed to meet John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Jacqueline Lee Bouvier. That introduction came when Hy Peskin photographed the handsome politician on the make and his radiant fiancée over a summer weekend in 1953. Peskin, a renowned sports photographer, headed to Hyannis Port, Mass., at the invitation of family patriarch Joseph Kennedy. The ambassador, eager for his son to take the stage as a national figure, thought a feature in the pages of LIFE would foster a fascination with John, his pretty girlfriend and one of America’s wealthiest families. That it did. Peskin put together a somewhat contrived “behind the scenes” series titled “Senator Kennedy Goes A-Courting.” While Jackie bristled at the intrusion—John’s mother Rose even told her how to pose—she went along with the staging, and readers got to observe Jackie mussing the hair of “the handsomest young member of the U.S. Senate,” playing football and softball with her future in-laws, and sailing aboard John’s boat, Victura. “They just shoved me into that boat long enough to take the picture,” she later confided to a friend. It was pitch-perfect brand making, with Kennedy on the cover of the world’s most widely read photo magazine, cast as a self-assured playboy prepared to say goodbye to bachelorhood. A few months later LIFE would cover the couple’s wedding, and by then America was captivated. In the staid age of Dwight David Eisenhower and Richard Milhous Nixon, Peskin unveiled the face of Camelot, one that changed America’s perception of politics and politicians, and set John and Jackie off on becoming the most recognizable couple on the planet. -

10.

Birmingham, Alabama, Charles Moore, 1963. Sometimes the most effective mirror is a photograph. In the summer of 1963, Birmingham was boiling over as black residents and their allies in the civil rights movement repeatedly clashed with a white power structure intent on maintaining segregation—and willing to do whatever that took. A photographer for the Montgomery Advertiser and life, Charles Moore was a native Alabaman and son of a Baptist preacher appalled by the violence inflicted on African Americans in the name of law and order. Though he photographed many other seminal moments of the movement, it was Moore’s image of a police dog tearing into a black protester’s pants that captured the routine, even casual, brutality of segregation. When the picture was published in life, it quickly became apparent to the rest of the world what Moore had long known: ending segregation was not about eroding culture but about restoring humanity. Hesitant politicians soon took up the cause and passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 nearly a year later.

Birmingham, Alabama, Charles Moore, 1963. Sometimes the most effective mirror is a photograph. In the summer of 1963, Birmingham was boiling over as black residents and their allies in the civil rights movement repeatedly clashed with a white power structure intent on maintaining segregation—and willing to do whatever that took. A photographer for the Montgomery Advertiser and life, Charles Moore was a native Alabaman and son of a Baptist preacher appalled by the violence inflicted on African Americans in the name of law and order. Though he photographed many other seminal moments of the movement, it was Moore’s image of a police dog tearing into a black protester’s pants that captured the routine, even casual, brutality of segregation. When the picture was published in life, it quickly became apparent to the rest of the world what Moore had long known: ending segregation was not about eroding culture but about restoring humanity. Hesitant politicians soon took up the cause and passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 nearly a year later. -

11.

Grief, Dmitri Baltermants, 1942. The Polish-born Dmitri Baltermants had planned to be a math teacher but instead fell in love with photography. Just as World War II broke out, he got a call from his bosses at the Soviet government paper Izvestia: “Our troops are crossing the border tomorrow. Get ready to shoot the annexation of western Ukraine!” At the time the Soviet Union considered Nazi Germany its ally. But after Adolf Hitler turned on his comrades and invaded the Soviet Union, Baltermants’ mission changed too. Covering what then became known as the Great Patriotic War, he captured grim images of body-littered roads along with those of troops enjoying quiet moments. In January 1942 he was in the newly liberated city of Kerch, Crimea, where two months earlier Nazi death squads had rounded up the town’s 7,000 Jews. “They drove out whole families—women, the elderly, children,” Baltermants recalled years later. “They drove all of them to an antitank ditch and shot them.” There Baltermants came upon a bleak, corpse-choked field, the outstretched limbs of old and young alike frozen in the last moment of pleading. Some of the gathered townspeople wailed, their arms wide. Others hunched in paroxysms of grief. Baltermants, who witnessed more than his share of death, recorded what he saw. Yet these images of mass Nazi murders on Soviet soil were too graphic for his nation’s leaders, wary of displaying the suffering of their people. Like many of Baltermants’ photos, this one was censored, being shown only decades later as liberalism seeped into Russian society in the 1960s. When it finally emerged, Baltermants’ picture allowed generations of Russians to form a collective memory of their great war. “You do your work the best you can,” he somberly observed, “and someday it will surface.”

Grief, Dmitri Baltermants, 1942. The Polish-born Dmitri Baltermants had planned to be a math teacher but instead fell in love with photography. Just as World War II broke out, he got a call from his bosses at the Soviet government paper Izvestia: “Our troops are crossing the border tomorrow. Get ready to shoot the annexation of western Ukraine!” At the time the Soviet Union considered Nazi Germany its ally. But after Adolf Hitler turned on his comrades and invaded the Soviet Union, Baltermants’ mission changed too. Covering what then became known as the Great Patriotic War, he captured grim images of body-littered roads along with those of troops enjoying quiet moments. In January 1942 he was in the newly liberated city of Kerch, Crimea, where two months earlier Nazi death squads had rounded up the town’s 7,000 Jews. “They drove out whole families—women, the elderly, children,” Baltermants recalled years later. “They drove all of them to an antitank ditch and shot them.” There Baltermants came upon a bleak, corpse-choked field, the outstretched limbs of old and young alike frozen in the last moment of pleading. Some of the gathered townspeople wailed, their arms wide. Others hunched in paroxysms of grief. Baltermants, who witnessed more than his share of death, recorded what he saw. Yet these images of mass Nazi murders on Soviet soil were too graphic for his nation’s leaders, wary of displaying the suffering of their people. Like many of Baltermants’ photos, this one was censored, being shown only decades later as liberalism seeped into Russian society in the 1960s. When it finally emerged, Baltermants’ picture allowed generations of Russians to form a collective memory of their great war. “You do your work the best you can,” he somberly observed, “and someday it will surface.” -

12.

The Falling Soldier, Robert Capa, 1936. Robert Capa made his seminal photograph of the Spanish Civil War without ever looking through his viewfinder. Widely considered one of the best combat photographs ever made, and the first to show battlefield death in action, Capa said in a 1947 radio interview that he was in the trenches with Republican militiamen. The men would pop aboveground to charge and fire old rifles at a machine gun manned by troops loyal to Francisco Franco. Each time, the militiamen would get gunned down. During one charge, Capa held his camera above his head and clicked the shutter. The result is an image that is full of drama and movement as the shot soldier tumbles backward. In the 1970s, decades after it was published in the French magazine Vu and LIFE, a South African journalist named O.D. Gallagher claimed that Capa had told him the image was staged. But no confirmation was ever presented, and most believe that Capa’s is a genuine candid photograph of a Spanish militiaman being shot. Capa’s image elevated war photography to a new level long before journalists were formally embedded with combat troops, showing how crucial, if dangerous, it is for photographers to be in the middle of the action.

The Falling Soldier, Robert Capa, 1936. Robert Capa made his seminal photograph of the Spanish Civil War without ever looking through his viewfinder. Widely considered one of the best combat photographs ever made, and the first to show battlefield death in action, Capa said in a 1947 radio interview that he was in the trenches with Republican militiamen. The men would pop aboveground to charge and fire old rifles at a machine gun manned by troops loyal to Francisco Franco. Each time, the militiamen would get gunned down. During one charge, Capa held his camera above his head and clicked the shutter. The result is an image that is full of drama and movement as the shot soldier tumbles backward. In the 1970s, decades after it was published in the French magazine Vu and LIFE, a South African journalist named O.D. Gallagher claimed that Capa had told him the image was staged. But no confirmation was ever presented, and most believe that Capa’s is a genuine candid photograph of a Spanish militiaman being shot. Capa’s image elevated war photography to a new level long before journalists were formally embedded with combat troops, showing how crucial, if dangerous, it is for photographers to be in the middle of the action. -

13.

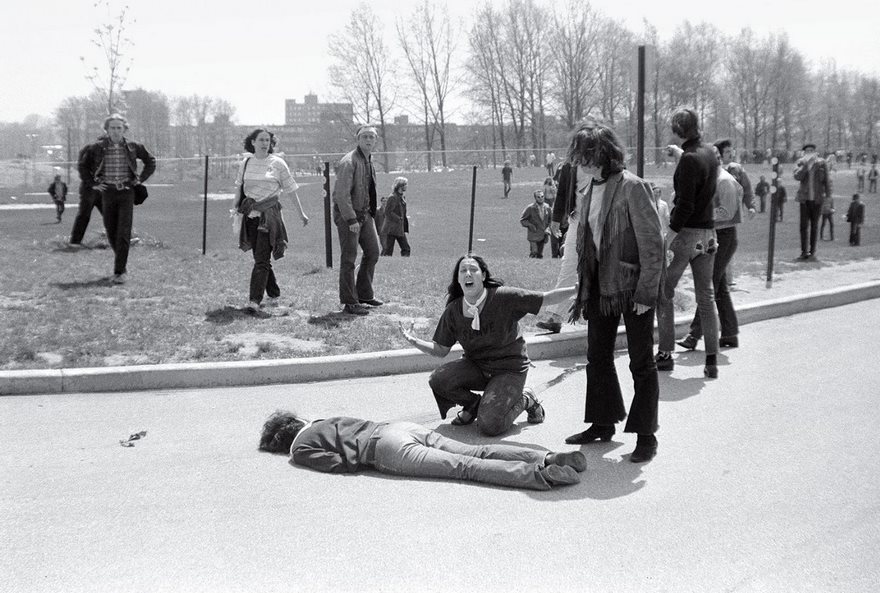

Kent State Shootings, John Paul Filo, 1970. The shooting at Kent State University in Ohio lasted 13 seconds. When it was over, four students were dead, nine were wounded, and the innocence of a generation was shattered. The demonstrators were part of a national wave of student discontent spurred by the new presence of U.S. troops in Cambodia. At the Kent State Commons, protesters assumed that the National Guard troops that had been called to contain the crowds were firing blanks. But when the shooting stopped and students lay dead, it seemed that the war in Southeast Asia had come home. John Filo, a student and part-time news photographer, distilled that feeling into a single image when he captured Mary Ann Vecchio crying out and kneeling over a fatally wounded Jeffrey Miller. Filo’s photograph was put out on the AP wire and printed on the front page of the New York Times. It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize and has since become the visual symbol of a hopeful nation’s lost youth. As Neil Young wrote in the song “Ohio,” inspired by a LIFE story featuring Filo’s images, “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming/ We’re finally on our own/ This summer I hear the drumming/ Four dead in Ohio.”

Kent State Shootings, John Paul Filo, 1970. The shooting at Kent State University in Ohio lasted 13 seconds. When it was over, four students were dead, nine were wounded, and the innocence of a generation was shattered. The demonstrators were part of a national wave of student discontent spurred by the new presence of U.S. troops in Cambodia. At the Kent State Commons, protesters assumed that the National Guard troops that had been called to contain the crowds were firing blanks. But when the shooting stopped and students lay dead, it seemed that the war in Southeast Asia had come home. John Filo, a student and part-time news photographer, distilled that feeling into a single image when he captured Mary Ann Vecchio crying out and kneeling over a fatally wounded Jeffrey Miller. Filo’s photograph was put out on the AP wire and printed on the front page of the New York Times. It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize and has since become the visual symbol of a hopeful nation’s lost youth. As Neil Young wrote in the song “Ohio,” inspired by a LIFE story featuring Filo’s images, “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming/ We’re finally on our own/ This summer I hear the drumming/ Four dead in Ohio.” -

14.

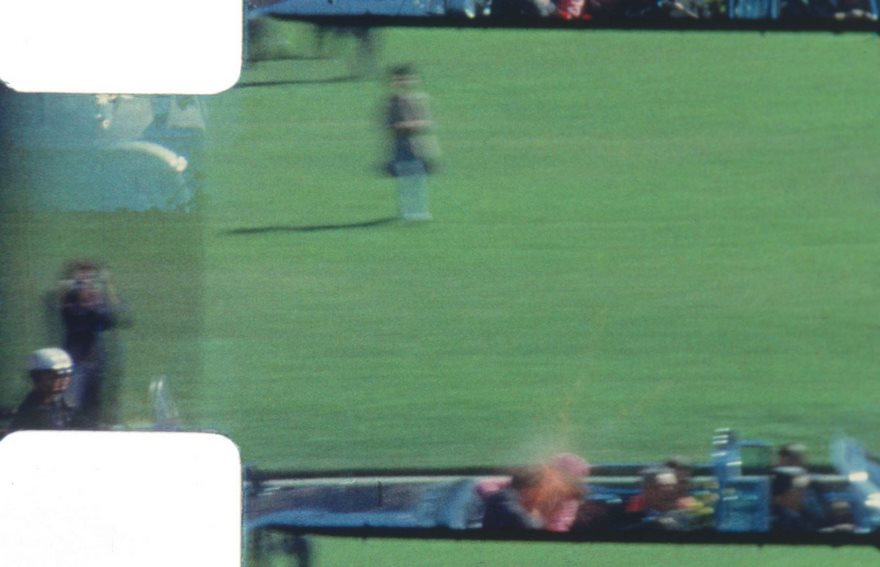

JFK Assassination, Frame 313, Abraham Zapruder, 1963. It is the most famous home movie ever, and the most carefully studied image, an 8-millimeter film that captured the death of a President. The movie is just as well known for what many say it does or does not reveal, and its existence has fostered countless conspiracy theories about that day in Dallas. But no one would argue that what it shows is not utterly heartbreaking, the last moments of life of the youthful and charismatic John Fitzgerald Kennedy as he rode with his wife Jackie through Dealey Plaza. Amateur photographer Abraham Zapruder had eagerly set out with his Bell & Howell camera on the morning of November 22, 1963, to record the arrival of his hero. Yet as Zapruder filmed, one bullet struck Kennedy in the back, and as the President’s car passed in front of Zapruder, a second one hit him in the head. LIFE correspondent Richard Stolley bought the film the following day, and the magazine ran 31 of the 486 frames—which meant that the first public viewing of Zapruder’s famous film was as a series of still images. At the time, LIFE withheld the gruesome frame No. 313—a picture that became influential by its absence. That one, where the bullet exploded the side of Kennedy’s head, is still shocking when seen today, a reminder of the seeming suddenness of death. What Zapruder captured that sunny day would haunt him for the rest of his life. It is something that unsettles America, a dark dream that hovers at the back of our collective psyche, an image from a wisp of 26.5 seconds of film whose gut-wrenching impact reminds us how everything can change in a fraction of a moment.

JFK Assassination, Frame 313, Abraham Zapruder, 1963. It is the most famous home movie ever, and the most carefully studied image, an 8-millimeter film that captured the death of a President. The movie is just as well known for what many say it does or does not reveal, and its existence has fostered countless conspiracy theories about that day in Dallas. But no one would argue that what it shows is not utterly heartbreaking, the last moments of life of the youthful and charismatic John Fitzgerald Kennedy as he rode with his wife Jackie through Dealey Plaza. Amateur photographer Abraham Zapruder had eagerly set out with his Bell & Howell camera on the morning of November 22, 1963, to record the arrival of his hero. Yet as Zapruder filmed, one bullet struck Kennedy in the back, and as the President’s car passed in front of Zapruder, a second one hit him in the head. LIFE correspondent Richard Stolley bought the film the following day, and the magazine ran 31 of the 486 frames—which meant that the first public viewing of Zapruder’s famous film was as a series of still images. At the time, LIFE withheld the gruesome frame No. 313—a picture that became influential by its absence. That one, where the bullet exploded the side of Kennedy’s head, is still shocking when seen today, a reminder of the seeming suddenness of death. What Zapruder captured that sunny day would haunt him for the rest of his life. It is something that unsettles America, a dark dream that hovers at the back of our collective psyche, an image from a wisp of 26.5 seconds of film whose gut-wrenching impact reminds us how everything can change in a fraction of a moment. -

15.

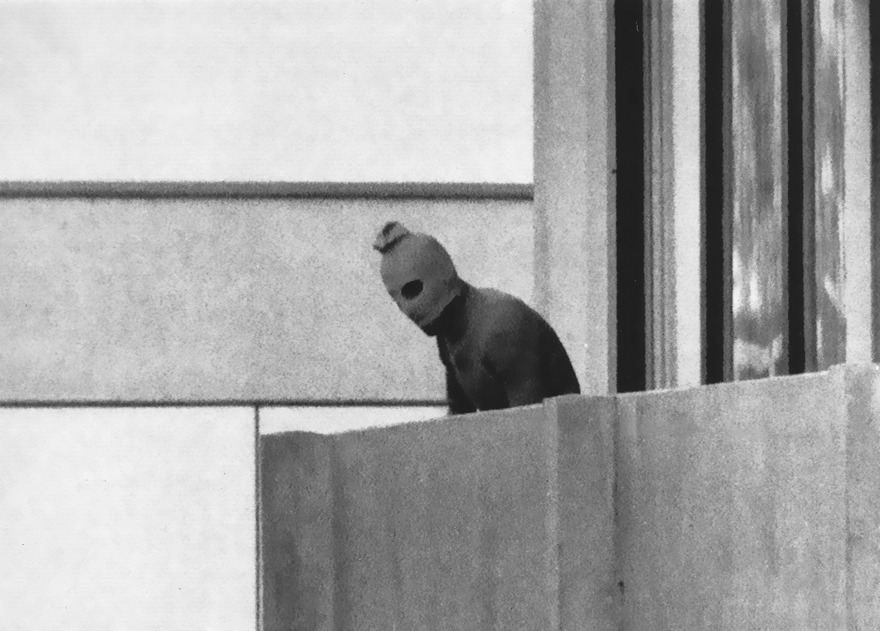

Munich Massacre, Kurt Strumpf, 1972. The Olympics celebrate the best of humanity, and in 1972 Germany welcomed the Games to exalt its athletes, tout its democracy and purge the stench of Adolf Hitler’s 1936 Games. The Germans called it “the Games of peace and joy,” and as Israeli fencer Dan Alon recalled, “Taking part in the opening ceremony, only 36 years after Berlin, was one of the most beautiful moments in my life.” Security was lax so as to project the feeling of harmony. Unfortunately, this made it easy on September 5 for eight members of the Palestinian terrorist group Black September to raid the Munich Olympic Village building housing Israeli Olympians. Armed with grenades and assault rifles, the terrorists killed two team members, took nine hostage and demanded the release of 234 of their jailed compatriots. The 21-hour hostage standoff presented the world with its first live window on terrorism, and 900 million people tuned in. During the siege, one of the Black Septemberists made his way out onto the apartment’s balcony. As he did, Associated Press photographer Kurt Strumpf froze this haunting image, the faceless look of terror. As the Palestinians attempted to flee, German snipers tried to take them out, and the Palestinians killed the hostages and a policeman. The already fraught Arab-Israeli relationship became even more so, and the siege led to retaliatory attacks on Palestinian bases. Strumpf’s photo of that specter with cut-out eyes is a sobering reminder of how we were all diminished when the world realized that nothing was secure.

Munich Massacre, Kurt Strumpf, 1972. The Olympics celebrate the best of humanity, and in 1972 Germany welcomed the Games to exalt its athletes, tout its democracy and purge the stench of Adolf Hitler’s 1936 Games. The Germans called it “the Games of peace and joy,” and as Israeli fencer Dan Alon recalled, “Taking part in the opening ceremony, only 36 years after Berlin, was one of the most beautiful moments in my life.” Security was lax so as to project the feeling of harmony. Unfortunately, this made it easy on September 5 for eight members of the Palestinian terrorist group Black September to raid the Munich Olympic Village building housing Israeli Olympians. Armed with grenades and assault rifles, the terrorists killed two team members, took nine hostage and demanded the release of 234 of their jailed compatriots. The 21-hour hostage standoff presented the world with its first live window on terrorism, and 900 million people tuned in. During the siege, one of the Black Septemberists made his way out onto the apartment’s balcony. As he did, Associated Press photographer Kurt Strumpf froze this haunting image, the faceless look of terror. As the Palestinians attempted to flee, German snipers tried to take them out, and the Palestinians killed the hostages and a policeman. The already fraught Arab-Israeli relationship became even more so, and the siege led to retaliatory attacks on Palestinian bases. Strumpf’s photo of that specter with cut-out eyes is a sobering reminder of how we were all diminished when the world realized that nothing was secure. -

16.

Winston Churchill, Yousuf Karsh, 1941. Britain stood alone in 1941. By then Poland, France and large parts of Europe had fallen to the Nazi forces, and it was only the tiny nation’s pilots, soldiers and sailors, along with those of the Commonwealth, who kept the darkness at bay. Winston Churchill was determined that the light of England would continue to shine. In December 1941, soon after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America was pulled into the war, Churchill visited Parliament in Ottawa to thank Canada and the Allies for their help. Churchill wasn’t aware that Yousuf Karsh had been tasked to take his portrait afterward, and when he came out and saw the Turkish-born Canadian photographer, he demanded to know, “Why was I not told?” Churchill then lit a cigar, puffed at it and said to the photographer, “You may take one.” As Karsh prepared, Churchill refused to put down the cigar. So once Karsh made sure all was ready, he walked over to the Prime Minister and said, “Forgive me, sir,” and plucked the cigar out of Churchill’s mouth. “By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent, he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.” Ever the diplomat, Churchill then smiled and said, “You may take another one” and shook Karsh’s hand, telling him, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.” The result of Karsh’s lion taming is one of the most widely reproduced images in history and a watershed in the art of political portraiture. It was Karsh’s picture of the bulldoggish Churchill—published first in the American daily PM and eventually on the cover of LIFE—that gave modern photographers permission to make honest, even critical portrayals of our leaders.

Winston Churchill, Yousuf Karsh, 1941. Britain stood alone in 1941. By then Poland, France and large parts of Europe had fallen to the Nazi forces, and it was only the tiny nation’s pilots, soldiers and sailors, along with those of the Commonwealth, who kept the darkness at bay. Winston Churchill was determined that the light of England would continue to shine. In December 1941, soon after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America was pulled into the war, Churchill visited Parliament in Ottawa to thank Canada and the Allies for their help. Churchill wasn’t aware that Yousuf Karsh had been tasked to take his portrait afterward, and when he came out and saw the Turkish-born Canadian photographer, he demanded to know, “Why was I not told?” Churchill then lit a cigar, puffed at it and said to the photographer, “You may take one.” As Karsh prepared, Churchill refused to put down the cigar. So once Karsh made sure all was ready, he walked over to the Prime Minister and said, “Forgive me, sir,” and plucked the cigar out of Churchill’s mouth. “By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent, he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.” Ever the diplomat, Churchill then smiled and said, “You may take another one” and shook Karsh’s hand, telling him, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.” The result of Karsh’s lion taming is one of the most widely reproduced images in history and a watershed in the art of political portraiture. It was Karsh’s picture of the bulldoggish Churchill—published first in the American daily PM and eventually on the cover of LIFE—that gave modern photographers permission to make honest, even critical portrayals of our leaders. -

17.

The Dead Of Antietam, Alexander Gardner, 1862. It was at Antietam, the blood-churning battle in Sharpsburg, Md., where more Americans died in a single day than ever had before, that one Union soldier recalled how “the piles of dead ... were frightful.” The Scottish-born photographer Alexander Gardner arrived there two days after the September 17, 1862, slaughter. He set up his stereo wet-plate camera and started taking dozens of images of the body-strewn countryside, documenting fallen soldiers, burial crews and trench graves. Gardner worked for Mathew Brady, and when he returned to New York City his employer arranged an exhibition of the work. Visitors were greeted with a plain sign reading “The Dead of Antietam.” But what they saw was anything but simple. Genteel society came upon what are believed to be the first recorded images of war casualties. Gardner’s photographs are so sharp that people could make out faces. The death was unfiltered, and a war that had seemed remote suddenly became harrowingly immediate. Gardner helped make Americans realize the significance of the fratricide that by 1865 would take more than 600,000 lives. For in the hallowed fields fell not faceless strangers but sons, brothers, fathers, cousins and friends. And Gardner’s images of Antietam created a lasting legacy by establishing a painfully potent visual precedent for the way all wars have since been covered.

The Dead Of Antietam, Alexander Gardner, 1862. It was at Antietam, the blood-churning battle in Sharpsburg, Md., where more Americans died in a single day than ever had before, that one Union soldier recalled how “the piles of dead ... were frightful.” The Scottish-born photographer Alexander Gardner arrived there two days after the September 17, 1862, slaughter. He set up his stereo wet-plate camera and started taking dozens of images of the body-strewn countryside, documenting fallen soldiers, burial crews and trench graves. Gardner worked for Mathew Brady, and when he returned to New York City his employer arranged an exhibition of the work. Visitors were greeted with a plain sign reading “The Dead of Antietam.” But what they saw was anything but simple. Genteel society came upon what are believed to be the first recorded images of war casualties. Gardner’s photographs are so sharp that people could make out faces. The death was unfiltered, and a war that had seemed remote suddenly became harrowingly immediate. Gardner helped make Americans realize the significance of the fratricide that by 1865 would take more than 600,000 lives. For in the hallowed fields fell not faceless strangers but sons, brothers, fathers, cousins and friends. And Gardner’s images of Antietam created a lasting legacy by establishing a painfully potent visual precedent for the way all wars have since been covered. -

18.

Bosnia, Ron Haviv, 1992. It can take time for even the most shocking images to have an effect. The war in Bosnia had not yet begun when American Ron Haviv took this picture of a Serb kicking a Muslim woman who had been shot by Serb forces. Haviv had gained access to the Tigers, a brutal nationalist militia that had warned him not to photograph any killings. But Haviv was determined to document the cruelty he was witnessing and, in a split second, decided to risk it. TIME published the photo a week later, and the image of casual hatred ignited broad debate over the international response to the worsening conflict. Still, the war continued for more than three years, and Haviv—who was put on a hit list by the Tigers’ leader, Zeljko Raznatovic, or Arkan—was frustrated by the tepid reaction. Almost 100,000 people lost their lives. Before his assassination in 2000, Arkan was indicted for crimes against humanity. Haviv’s image was used as evidence against him and other perpetrators of what became known as ethnic cleansing.

Bosnia, Ron Haviv, 1992. It can take time for even the most shocking images to have an effect. The war in Bosnia had not yet begun when American Ron Haviv took this picture of a Serb kicking a Muslim woman who had been shot by Serb forces. Haviv had gained access to the Tigers, a brutal nationalist militia that had warned him not to photograph any killings. But Haviv was determined to document the cruelty he was witnessing and, in a split second, decided to risk it. TIME published the photo a week later, and the image of casual hatred ignited broad debate over the international response to the worsening conflict. Still, the war continued for more than three years, and Haviv—who was put on a hit list by the Tigers’ leader, Zeljko Raznatovic, or Arkan—was frustrated by the tepid reaction. Almost 100,000 people lost their lives. Before his assassination in 2000, Arkan was indicted for crimes against humanity. Haviv’s image was used as evidence against him and other perpetrators of what became known as ethnic cleansing. -

19.

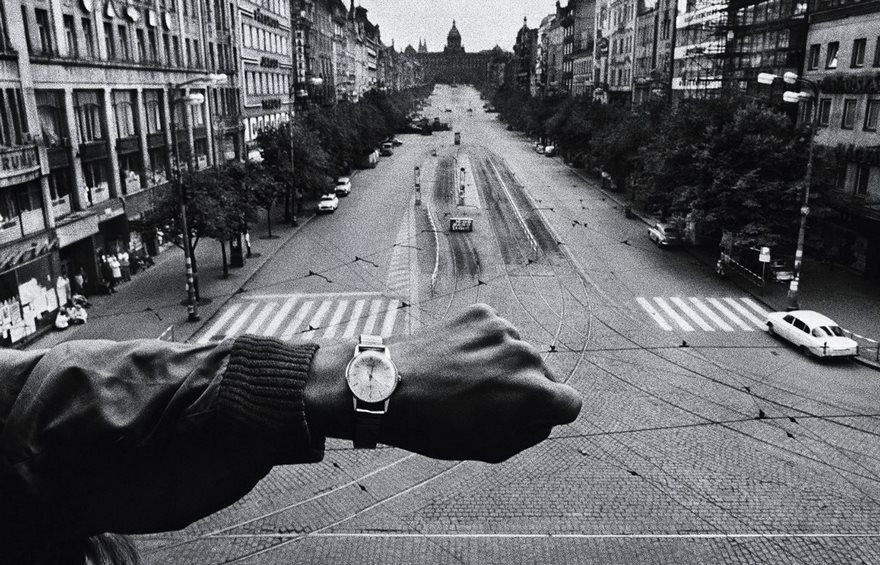

Invasion Of Prague, Josef Koudelka, 1968. The Soviets did not care for the “socialism with a human face” that Alexander Dubcek’s government brought to Czechoslovakia. Fearing that Dubcek’s human-rights reforms would lead to a democratic uprising like the one in Hungary in 1956, Warsaw Bloc forces set out to quash the movement. Their tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968. And while they quickly seized control of Prague, they unexpectedly ran up against masses of flag-waving citizens who threw up barricades, stoned tanks, overturned trucks and even removed street signs in order to confuse the troops. Josef Koudelka, a young Moravian-born engineer who had been taking wistful and gritty photos of Czech life, was in the capital when the soldiers arrived. He took pictures of the swirling turmoil and created a groundbreaking record of the invasion that would change the course of his nation. The most seminal piece includes a man’s arm in the foreground, showing on his wristwatch a moment of the Soviet invasion with a deserted street in the distance. It beautifully encapsulates time, loss and emptiness—and the strangling of a society. Koudelka’s visual memories of the unfolding conflict—with its evidence of the ticking time, the brutality of the attack and the challenges by Czech citizens—redefined photojournalism. His pictures were smuggled out of Czechoslovakia and appeared in the London Sunday Times in 1969, though under the pseudonym P.P. for Prague Photographer since Koudelka feared reprisals. He soon fled, his rationale for leaving the country a testament to the power of photographic evidence: “I was afraid to go back to Czechoslovakia because I knew that if they wanted to find out who the unknown photographer was, they could do it.”

Invasion Of Prague, Josef Koudelka, 1968. The Soviets did not care for the “socialism with a human face” that Alexander Dubcek’s government brought to Czechoslovakia. Fearing that Dubcek’s human-rights reforms would lead to a democratic uprising like the one in Hungary in 1956, Warsaw Bloc forces set out to quash the movement. Their tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968. And while they quickly seized control of Prague, they unexpectedly ran up against masses of flag-waving citizens who threw up barricades, stoned tanks, overturned trucks and even removed street signs in order to confuse the troops. Josef Koudelka, a young Moravian-born engineer who had been taking wistful and gritty photos of Czech life, was in the capital when the soldiers arrived. He took pictures of the swirling turmoil and created a groundbreaking record of the invasion that would change the course of his nation. The most seminal piece includes a man’s arm in the foreground, showing on his wristwatch a moment of the Soviet invasion with a deserted street in the distance. It beautifully encapsulates time, loss and emptiness—and the strangling of a society. Koudelka’s visual memories of the unfolding conflict—with its evidence of the ticking time, the brutality of the attack and the challenges by Czech citizens—redefined photojournalism. His pictures were smuggled out of Czechoslovakia and appeared in the London Sunday Times in 1969, though under the pseudonym P.P. for Prague Photographer since Koudelka feared reprisals. He soon fled, his rationale for leaving the country a testament to the power of photographic evidence: “I was afraid to go back to Czechoslovakia because I knew that if they wanted to find out who the unknown photographer was, they could do it.” -

20.

American Gothic, Gordon Parks, 1942. As the 15th child of black Kansas sharecroppers, Gordon Parks knew poverty. But he didn’t experience virulent racism until he arrived in Washington in 1942 for a fellowship at the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Parks, who would go on to became the first African-American photographer at LIFE, was stunned. “White restaurants made me enter through the back door. White theaters wouldn’t even let me in the door,” he recalled. Refusing to be cowed, Parks searched out older African Americans to document how they dealt with such daily indignities and came across Ella Watson, who worked in the FSA’s building. She told him of her life of struggle, of a father murdered by a lynch mob, of a husband shot to death. He photographed Watson as she went about her day, culminating in his American Gothic, a clear parody of Grant Wood’s iconic 1930 oil painting. It served as an indictment of the treatment of African Americans by accentuating the inequality in “the land of the free” and came to symbolize life in pre-civil-rights America. “What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism,” Parks later observed, “by showing the people who suffered most under it.”

American Gothic, Gordon Parks, 1942. As the 15th child of black Kansas sharecroppers, Gordon Parks knew poverty. But he didn’t experience virulent racism until he arrived in Washington in 1942 for a fellowship at the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Parks, who would go on to became the first African-American photographer at LIFE, was stunned. “White restaurants made me enter through the back door. White theaters wouldn’t even let me in the door,” he recalled. Refusing to be cowed, Parks searched out older African Americans to document how they dealt with such daily indignities and came across Ella Watson, who worked in the FSA’s building. She told him of her life of struggle, of a father murdered by a lynch mob, of a husband shot to death. He photographed Watson as she went about her day, culminating in his American Gothic, a clear parody of Grant Wood’s iconic 1930 oil painting. It served as an indictment of the treatment of African Americans by accentuating the inequality in “the land of the free” and came to symbolize life in pre-civil-rights America. “What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism,” Parks later observed, “by showing the people who suffered most under it.” -

21.

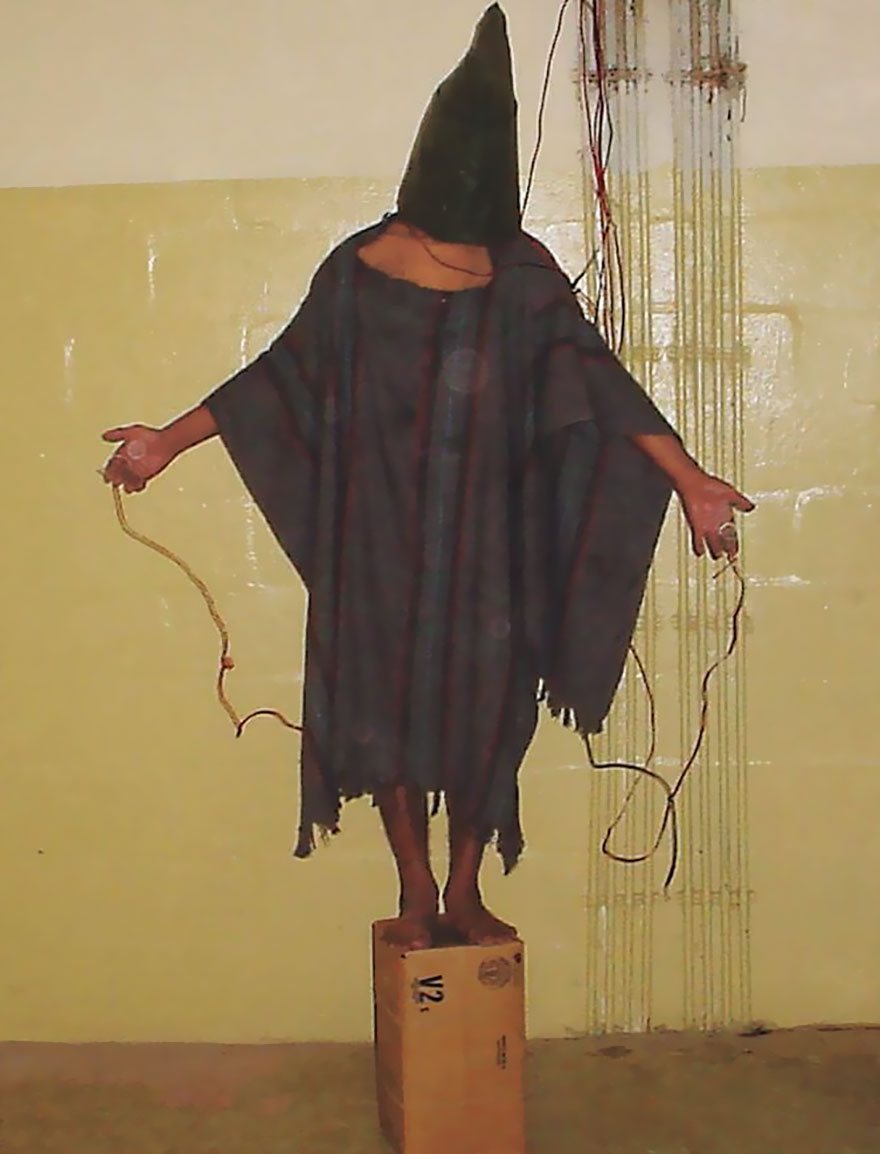

The Hooded Man, Sergeant Ivan Frederick, 2003. Hundreds of photojournalists covered the conflict in Iraq, but the most memorable image from the war was taken not by a professional but by a U.S. Army staff sergeant named Ivan Frederick. In the last three months of 2003, Frederick was the senior enlisted man at Abu Ghraib prison, the facility on the outskirts of Baghdad that Saddam Hussein had made into a symbol of terror for all Iraqis, then being used by the U.S. military as a detention center for suspected insurgents. Even before the Iraq War began, many questioned the motives of the American, British and allied governments for the invasion that toppled Saddam. But nothing undermined the allies’ claim that they were helping bring democracy to the country more than the scandal at Abu Ghraib. Frederick was one of several soldiers who took part in the torture of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib. All the more incredible was that they took thousands of images of their mistreatment, humiliation and torture of detainees with digital cameras and shared the photographs. The most widely disseminated was “the Hooded Man,” partly because it was less explicit than many of the others and so could more easily appear in mainstream publications. The man with outstretched arms in the photograph was deprived of his sight, his clothes, his dignity and, with electric wires, his sense of personal safety. And his pose? It seemed deliberately, unnervingly Christlike. The liberating invaders, it seemed, held nothing sacred.

The Hooded Man, Sergeant Ivan Frederick, 2003. Hundreds of photojournalists covered the conflict in Iraq, but the most memorable image from the war was taken not by a professional but by a U.S. Army staff sergeant named Ivan Frederick. In the last three months of 2003, Frederick was the senior enlisted man at Abu Ghraib prison, the facility on the outskirts of Baghdad that Saddam Hussein had made into a symbol of terror for all Iraqis, then being used by the U.S. military as a detention center for suspected insurgents. Even before the Iraq War began, many questioned the motives of the American, British and allied governments for the invasion that toppled Saddam. But nothing undermined the allies’ claim that they were helping bring democracy to the country more than the scandal at Abu Ghraib. Frederick was one of several soldiers who took part in the torture of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib. All the more incredible was that they took thousands of images of their mistreatment, humiliation and torture of detainees with digital cameras and shared the photographs. The most widely disseminated was “the Hooded Man,” partly because it was less explicit than many of the others and so could more easily appear in mainstream publications. The man with outstretched arms in the photograph was deprived of his sight, his clothes, his dignity and, with electric wires, his sense of personal safety. And his pose? It seemed deliberately, unnervingly Christlike. The liberating invaders, it seemed, held nothing sacred. -

22.

The Loch Ness Monster, 1934. If the giraffe never existed, we’d have to invent it. It’s our nature to grow bored with the improbable but real and look for the impossible. So it is with the photo of what was said to be the Loch Ness monster, purportedly taken by British doctor Robert Wilson in April 1934. Wilson, however, had simply been enlisted to cover up an earlier fraud by wild-game hunter Marmaduke Wetherell, who had been sent to Scotland by London’s Daily Mail to bag the monster. There being no monster to bag, Wetherell brought home photos of hippo prints that he said belonged to Nessie. The Mail caught wise and discredited Wetherell, who then returned to the loch with a monster made out of a toy submarine. He and his son used Wilson, a respected physician, to lend the hoax credibility. The Mail endures; Wilson’s reputation doesn’t. The Loch Ness image is something of a lodestone for conspiracy theorists and fable seekers, as is the absolutely authentic picture of the famous face on Mars taken by the Viking probe in 1976. The thrill of that find lasted only until 1998, when the Mars Global Surveyor proved the face was, as NASA said, a topographic formation, one that by that time had been nearly windblown away. We were innocents in those sweet, pre-Photoshop days. Now we know better—and we trust nothing. The art of the fake has advanced, but the charm of it, like the Martian face, is all but gone.

The Loch Ness Monster, 1934. If the giraffe never existed, we’d have to invent it. It’s our nature to grow bored with the improbable but real and look for the impossible. So it is with the photo of what was said to be the Loch Ness monster, purportedly taken by British doctor Robert Wilson in April 1934. Wilson, however, had simply been enlisted to cover up an earlier fraud by wild-game hunter Marmaduke Wetherell, who had been sent to Scotland by London’s Daily Mail to bag the monster. There being no monster to bag, Wetherell brought home photos of hippo prints that he said belonged to Nessie. The Mail caught wise and discredited Wetherell, who then returned to the loch with a monster made out of a toy submarine. He and his son used Wilson, a respected physician, to lend the hoax credibility. The Mail endures; Wilson’s reputation doesn’t. The Loch Ness image is something of a lodestone for conspiracy theorists and fable seekers, as is the absolutely authentic picture of the famous face on Mars taken by the Viking probe in 1976. The thrill of that find lasted only until 1998, when the Mars Global Surveyor proved the face was, as NASA said, a topographic formation, one that by that time had been nearly windblown away. We were innocents in those sweet, pre-Photoshop days. Now we know better—and we trust nothing. The art of the fake has advanced, but the charm of it, like the Martian face, is all but gone. -

23.

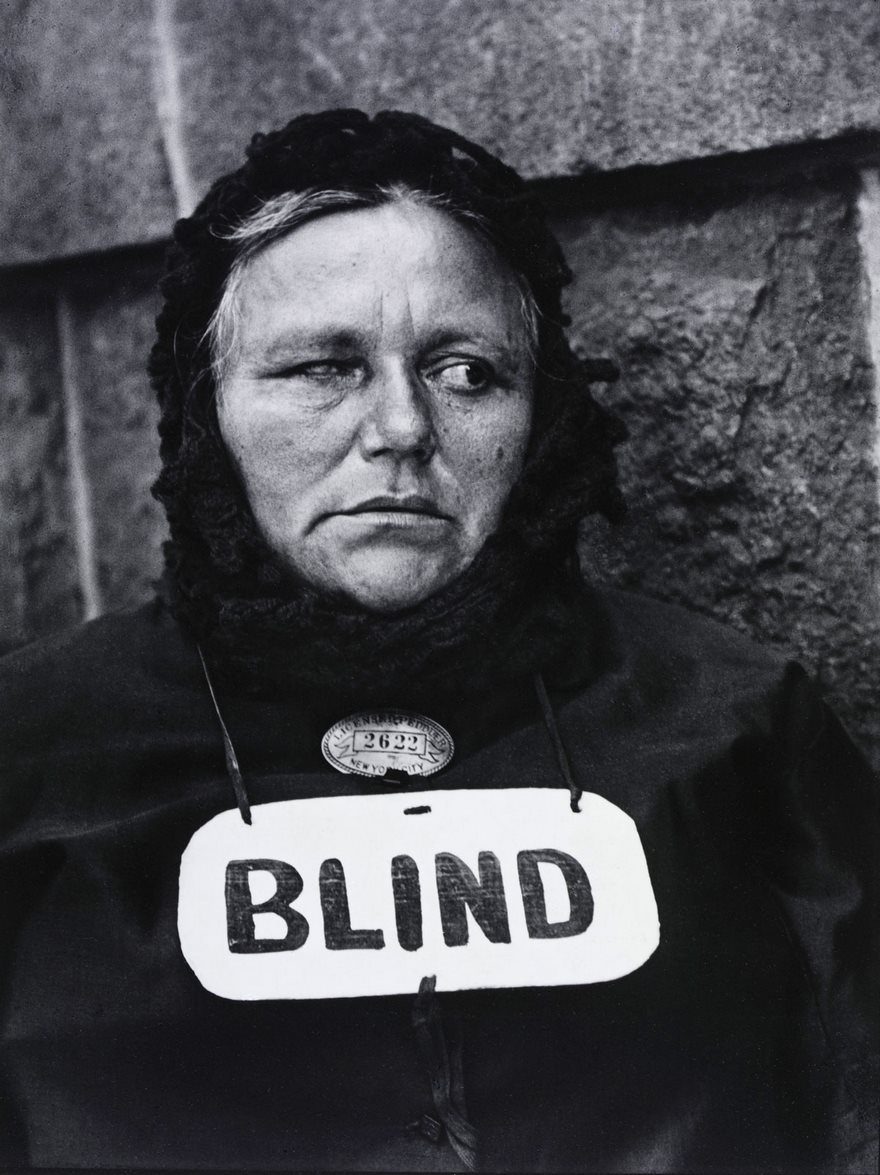

Blind, Paul Strand, 1916. Even if she could see, the woman in Paul Strand’s pioneering image might not have known she was being photographed. Strand wanted to capture people as they were, not as they projected themselves to be, and so when documenting immigrants on New York City’s Lower East Side, he used a false lens that allowed him to shoot in one direction even as his large camera was pointed in another. The result feels spontaneous and honest, a radical departure from the era’s formal portraits of people in stilted poses. Strand’s photograph of the blind woman, who he said was selling newspapers on the street, is candid, with the woman’s face turned away from the camera. But Strand’s work did more than offer an unflinching look at a moment when the nation was being reshaped by a surge of immigrants. By depicting subjects without their knowledge—or consent—and using their images to promote social awareness, Strand helped pave the way for an entirely new form of documentary art: street photography.

Blind, Paul Strand, 1916. Even if she could see, the woman in Paul Strand’s pioneering image might not have known she was being photographed. Strand wanted to capture people as they were, not as they projected themselves to be, and so when documenting immigrants on New York City’s Lower East Side, he used a false lens that allowed him to shoot in one direction even as his large camera was pointed in another. The result feels spontaneous and honest, a radical departure from the era’s formal portraits of people in stilted poses. Strand’s photograph of the blind woman, who he said was selling newspapers on the street, is candid, with the woman’s face turned away from the camera. But Strand’s work did more than offer an unflinching look at a moment when the nation was being reshaped by a surge of immigrants. By depicting subjects without their knowledge—or consent—and using their images to promote social awareness, Strand helped pave the way for an entirely new form of documentary art: street photography. -

24.

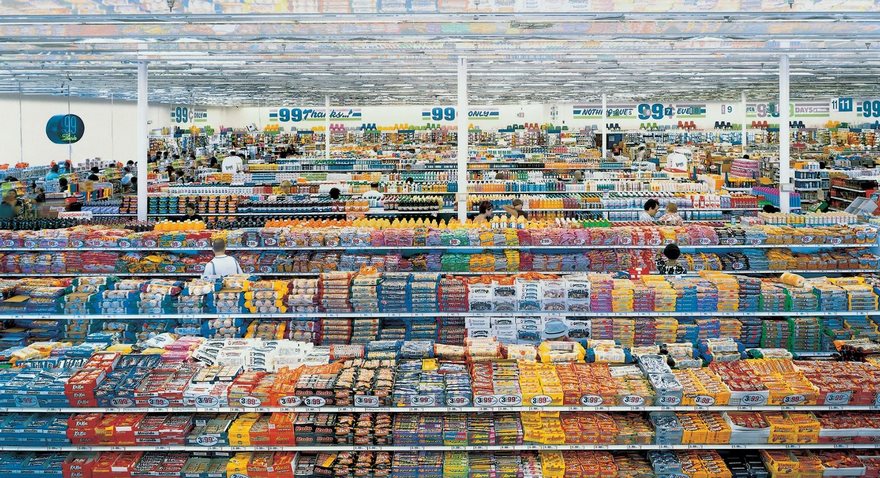

99 Cent, Andreas Gursky, 1999. It may seem ironic that a photograph of cheap goods would set a record for the most expensive contemporary photograph ever sold, but Andreas Gursky’s 99 Cent is far more than a visual inventory. In a single large-scale image digitally stitched together from multiple images taken in a 99 Cents Only store in Los Angeles, the seemingly endless rows of stuff, with shoppers’ heads floating anonymously above the merchandise, more closely resemble abstract or Impressionist painting than contemporary photography. Which was precisely Gursky’s point. From the Tokyo stock exchange to a Mexico City landfill, the German architect and photographer uses digital manipulation and a distinct sense of composition to turn everyday experiences into art. As the curator Peter Galassi wrote in the catalog for a 2001 retrospective of Gursky’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, “High art versus commerce, conceptual rigor versus spontaneous observation, photography versus painting ... for Gursky they are all givens—not opponents but companions.” That ability to render the man-made and mundane with fresh eyes has helped modern photography enter the art world’s elite. In 2006, in the heady days before the Great Recession, 99 Cent sold for $2.3 million at auction. The record for a contemporary photograph has since been surpassed, but the sale did more than any other to catapult modern photography into the pages of auction catalogs alongside the oil paintings and marble sculptures by old masters.

99 Cent, Andreas Gursky, 1999. It may seem ironic that a photograph of cheap goods would set a record for the most expensive contemporary photograph ever sold, but Andreas Gursky’s 99 Cent is far more than a visual inventory. In a single large-scale image digitally stitched together from multiple images taken in a 99 Cents Only store in Los Angeles, the seemingly endless rows of stuff, with shoppers’ heads floating anonymously above the merchandise, more closely resemble abstract or Impressionist painting than contemporary photography. Which was precisely Gursky’s point. From the Tokyo stock exchange to a Mexico City landfill, the German architect and photographer uses digital manipulation and a distinct sense of composition to turn everyday experiences into art. As the curator Peter Galassi wrote in the catalog for a 2001 retrospective of Gursky’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, “High art versus commerce, conceptual rigor versus spontaneous observation, photography versus painting ... for Gursky they are all givens—not opponents but companions.” That ability to render the man-made and mundane with fresh eyes has helped modern photography enter the art world’s elite. In 2006, in the heady days before the Great Recession, 99 Cent sold for $2.3 million at auction. The record for a contemporary photograph has since been surpassed, but the sale did more than any other to catapult modern photography into the pages of auction catalogs alongside the oil paintings and marble sculptures by old masters. -

25.

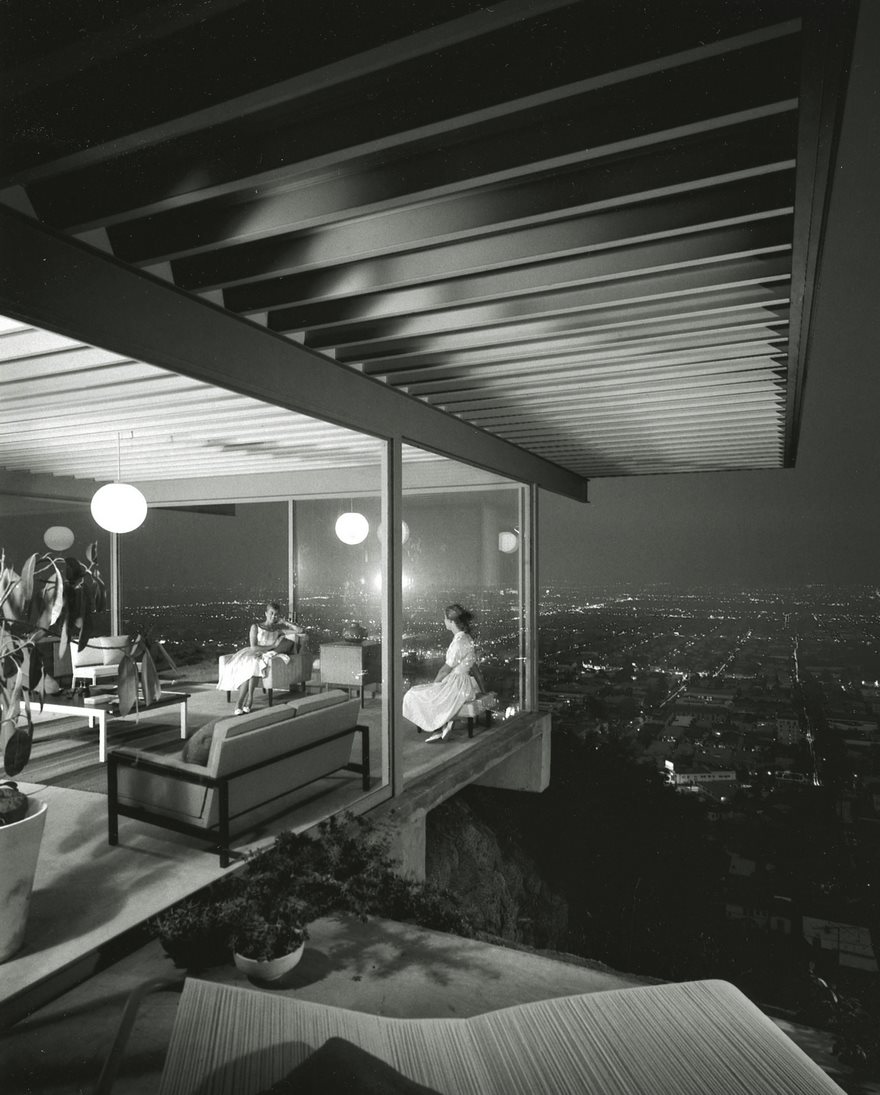

Case Study House No. 22, Los Angeles, Julius Shulman, 1960. For decades, the California Dream meant the chance to own a stucco home on a sliver of paradise. The point was the yard with the palm trees, not the contour of the walls. Julius Shulman helped change all that. In May 1960, the Brooklyn-born photographer headed to architect Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House, a glass-enclosed Hollywood Hills home with a breathtaking view of Los Angeles—one of 36 Case Study Houses that were part of an architectural experiment extolling the virtues of modernist theory and industrial materials. Shulman photographed most of the houses in the project, helping demystify modernism by highlighting its graceful simplicity and humanizing its angular edges. But none of his other pictures was more influential than the one he took of Case Study House No. 22. To show the essence of this air-breaking cantilevered building, Shulman set two glamorous women in cocktail dresses inside the house, where they appear to be floating above a mythic, twinkling city. The photo, which he called “one of my masterpieces,” is the most successful real estate image ever taken. It perfected the art of aspirational staging, turning a house into the embodiment of the Good Life, of stardusted Hollywood, of California as the Promised Land. And, thanks to Shulman, that dream now includes a glass box in the sky.

Case Study House No. 22, Los Angeles, Julius Shulman, 1960. For decades, the California Dream meant the chance to own a stucco home on a sliver of paradise. The point was the yard with the palm trees, not the contour of the walls. Julius Shulman helped change all that. In May 1960, the Brooklyn-born photographer headed to architect Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House, a glass-enclosed Hollywood Hills home with a breathtaking view of Los Angeles—one of 36 Case Study Houses that were part of an architectural experiment extolling the virtues of modernist theory and industrial materials. Shulman photographed most of the houses in the project, helping demystify modernism by highlighting its graceful simplicity and humanizing its angular edges. But none of his other pictures was more influential than the one he took of Case Study House No. 22. To show the essence of this air-breaking cantilevered building, Shulman set two glamorous women in cocktail dresses inside the house, where they appear to be floating above a mythic, twinkling city. The photo, which he called “one of my masterpieces,” is the most successful real estate image ever taken. It perfected the art of aspirational staging, turning a house into the embodiment of the Good Life, of stardusted Hollywood, of California as the Promised Land. And, thanks to Shulman, that dream now includes a glass box in the sky. -

26.

Betty Grable, Frank Powolny, 1943. Helen of Troy, the mythic Greek demigod who sparked the Trojan War and “launch’d a thousand ships,” had nothing on Betty Grable of St. Louis. For that platinum blond, blue-eyed Hollywood starlet had a set of gams that inspired American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines to set forth to save civilization from the Axis powers. And unlike Helen, Betty represented the flesh-and-blood “girl back home,” patiently keeping the fires burning. Frank Powolny brought Betty to the troops by accident. A photographer for 20th Century Fox, he was taking publicity pictures of the actress for the 1943 film Sweet Rosie O’Grady when she agreed to a “back shot.” The studio turned the coy pose into one of the earliest pinups, and soon troops were requesting 50,000 copies every month. The men took Betty wherever they went, tacking her poster to barrack walls, painting her on bomber fuselages and fastening 2-by-3 prints of her next to their hearts. Before Marilyn Monroe, Betty’s smile and legs—said to be insured for a million bucks with Lloyd’s of London—rallied countless homesick young men in the fight of their lives (including a young Hugh Hefner, who cited her as an inspiration for Playboy). “I’ve got to be an enlisted man’s girl,” said Grable, who signed hundreds of her pinups each month during the war. “Just like this has got to be an enlisted man’s war.”

Betty Grable, Frank Powolny, 1943. Helen of Troy, the mythic Greek demigod who sparked the Trojan War and “launch’d a thousand ships,” had nothing on Betty Grable of St. Louis. For that platinum blond, blue-eyed Hollywood starlet had a set of gams that inspired American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines to set forth to save civilization from the Axis powers. And unlike Helen, Betty represented the flesh-and-blood “girl back home,” patiently keeping the fires burning. Frank Powolny brought Betty to the troops by accident. A photographer for 20th Century Fox, he was taking publicity pictures of the actress for the 1943 film Sweet Rosie O’Grady when she agreed to a “back shot.” The studio turned the coy pose into one of the earliest pinups, and soon troops were requesting 50,000 copies every month. The men took Betty wherever they went, tacking her poster to barrack walls, painting her on bomber fuselages and fastening 2-by-3 prints of her next to their hearts. Before Marilyn Monroe, Betty’s smile and legs—said to be insured for a million bucks with Lloyd’s of London—rallied countless homesick young men in the fight of their lives (including a young Hugh Hefner, who cited her as an inspiration for Playboy). “I’ve got to be an enlisted man’s girl,” said Grable, who signed hundreds of her pinups each month during the war. “Just like this has got to be an enlisted man’s war.” -

27.

The Vanishing Race, Edward S. Curtis, 1904. Native Americans were the great casualty of the U.S.’s grand westward advance. As settlers tamed the seemingly boundless stretches of the young nation, they evicted Indians from their ancestral lands, shoving them into impoverished reservations and forcing them to assimilate. Fearing the imminent disappearance of America’s first inhabitants, Edward S. Curtis sought to document the assorted tribes, to show them as a noble people—“the old time Indian, his dress, his ceremonies, his life and manners.” Over more than two decades, Curtis turned these pictures and observations into The North American Indian, a 20-volume chronicle of 80 tribes. No single image embodied the project better than The Vanishing Race, his picture of Navajo riding off into the dusty distance. To Curtis the photo epitomized the plight of the Indians, who were “passing into the darkness of an unknown future.” Alas, Curtis’ encyclopedic work did more than convey the theme—it cemented a stereotype. Railroad companies soon lured tourists west with trips to glimpse the last of a dying people, and Indians came to be seen as a relic out of time, not an integral part of modern American society. It’s a perception that persists to this day.

The Vanishing Race, Edward S. Curtis, 1904. Native Americans were the great casualty of the U.S.’s grand westward advance. As settlers tamed the seemingly boundless stretches of the young nation, they evicted Indians from their ancestral lands, shoving them into impoverished reservations and forcing them to assimilate. Fearing the imminent disappearance of America’s first inhabitants, Edward S. Curtis sought to document the assorted tribes, to show them as a noble people—“the old time Indian, his dress, his ceremonies, his life and manners.” Over more than two decades, Curtis turned these pictures and observations into The North American Indian, a 20-volume chronicle of 80 tribes. No single image embodied the project better than The Vanishing Race, his picture of Navajo riding off into the dusty distance. To Curtis the photo epitomized the plight of the Indians, who were “passing into the darkness of an unknown future.” Alas, Curtis’ encyclopedic work did more than convey the theme—it cemented a stereotype. Railroad companies soon lured tourists west with trips to glimpse the last of a dying people, and Indians came to be seen as a relic out of time, not an integral part of modern American society. It’s a perception that persists to this day. -

28.

Bandit's Roost, Mulberry Street, Jacob Riis, Circa 1888. Late 19th-century New York City was a magnet for the world’s immigrants, and the vast majority of them found not streets paved with gold but nearly subhuman squalor. While polite society turned a blind eye, brave reporters like the Danish-born Jacob Riis documented this shame of the Gilded Age. Riis did this by venturing into the city’s most ominous neighborhoods with his blinding magnesium flash powder lights, capturing the casual crime, grinding poverty and frightful overcrowding. Most famous of these was Riis’ image of a Lower East Side street gang, which conveys the danger that lurked around every bend. Such work became the basis of his revelatory book How the Other Half Lives, which forced Americans to confront what they had long ignored and galvanized reformers like the young New York politician Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote to the photographer, “I have read your book, and I have come to help.” Riis’ work was instrumental in bringing about New York State’s landmark Tenement House Act of 1901, which improved conditions for the poor. And his crusading approach and direct, confrontational style ushered in the age of documentary and muckraking photojournalism.

Bandit's Roost, Mulberry Street, Jacob Riis, Circa 1888. Late 19th-century New York City was a magnet for the world’s immigrants, and the vast majority of them found not streets paved with gold but nearly subhuman squalor. While polite society turned a blind eye, brave reporters like the Danish-born Jacob Riis documented this shame of the Gilded Age. Riis did this by venturing into the city’s most ominous neighborhoods with his blinding magnesium flash powder lights, capturing the casual crime, grinding poverty and frightful overcrowding. Most famous of these was Riis’ image of a Lower East Side street gang, which conveys the danger that lurked around every bend. Such work became the basis of his revelatory book How the Other Half Lives, which forced Americans to confront what they had long ignored and galvanized reformers like the young New York politician Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote to the photographer, “I have read your book, and I have come to help.” Riis’ work was instrumental in bringing about New York State’s landmark Tenement House Act of 1901, which improved conditions for the poor. And his crusading approach and direct, confrontational style ushered in the age of documentary and muckraking photojournalism. -

29.